Looking for the bad guys

Today’s Courier Mail has an article about the Australian military casualties of the war that is the invasion of Iraq.

When we think “casualties of war” we often think of physical wounds- wheelchairs, scars and missing limbs. Forgotten and less visible casualties of war are the many Iraq veterans who are suffering from mental health issues. No prosthetics or empty trouser legs neatly pinned up out of the way for these men and women. What they endure, whilst not so obvious, is just as pervasive as a physical wound- involving gaps in cognition, coping, memory, connection and hopefulness.

The article states that approximately 6000 ADF troops have served in Iraq since the US-led invasion in 2003, and 52 have since been discharged with mental health conditions ranging from anxiety and depression to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Just imagine, 2 out of every 250 military personnel deployed to Iraq, in a period of 0-3 years after their return home, will end up having such a severe mental health issue that they will be classified as medically unfit and discharged from the ADF. No more military career.

The ADF will no doubt blame many factors other than the member’s deployment experience in Iraq for a veteran’s anxiety and depression diagnosis, and perhaps this can be justified. But what obfuscation will the department of defence attempt to dismiss the connection between the Iraq war and the prevalence of PTSD in its Iraqi veterans cohort? Unless a person has been raped or in a serious motor vehicle accident, then war is the most common cause of PSTD. Moreover, anxiety and depression have been shown to be co-morbid with a PTSD diagnosis. So, to knowingly deploy someone to Iraq who has/is suffering from anxiety and depression is negligent and may be actionable. The military is not caring for, or taking responsibility of, the mental health of its people.

I have a relative who voluntarily discharged from the army as soon as he could after the invasion of Iraq. He tells me he wishes that the army had lost him as well as they had found him which covers a period of a decade. He is in private practice and he knows a lot about Subjective Units of Discomfort Scale (SUDS) as he treats ex-military survivors of traumatic stress syndromes.

“I have no idea how what happened in Iraq did this to me, but I know I am not the same person I was before I went over. We lived, slept and breathed a highly stressful environment for six months. When I returned to Australia I was driving down the road looking for the bad guys – you start to realise how close to death you were.” – Gordon Traill.

Members of the ADF are still compliant, however in the UK, those that are refusing to kill are active and mobilised.

ADF chief psychologist Len Lambeth said the military “would be silly” to expect every soldier deployed to return home perfectly well. He said the rate of mental illness would be unlikely to decrease.

In the future refusing to obey lawful orders may be more successfully argued as a right to not be exposed to a psychological injury.

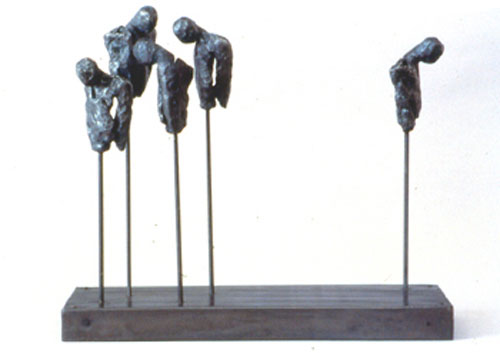

Image from here

May 21st, 2006 at 8:42 pm

You’d have thought the experiences of WW1, WW2, Korea and Vietnam veterans with PTSD would have taught the ADF something. But no. That’d be too easy – learning from experience.

May 21st, 2006 at 9:52 pm

I am not surprised that the ADF is 1500 short of its recruiting target.

I am also not surprised to see retention figures showing that members do not sign on for a further hitch past their initial 4 year enlistment (unless they are locked into a Return Of Service Obligation- ROSO) which equates to year-for-year for training plus one extra year.

May 24th, 2006 at 9:08 am

Suki, if more Aussie soldiers than just poor Jake Kovco had been killed in Iraq, you’d find that there’d be absolutely no new ADF recruits.

Up until 2003, quite a number of young Aussies signed up to the ADF for reasons similar to those of young Americans who joined the National Guard. Both groups rather thought that most of their assignments would be in natural disaster relief- not fighting an illegal war for control of oil.

ADF will have a very hard time retaining or recruiting until Iraq is as distant a memory as Vietnam.

May 25th, 2006 at 6:11 pm

If you look at the salary and the benefits and the training – especially the skilled trades program – you could understand why someone might join. But personally I have an objection to any line of work where the job description consists of meeting people, sometimes killing them and trying not getting killed in return.

May 29th, 2006 at 6:57 pm

Having had friends who went to Vietnam, I would say a lot of the stress in Iraq is the same, not knowing if the person next to you is friend or enemy. Even if they’re a friend there’s still resentment that you, a foreign soldier is in their country.

June 11th, 2006 at 10:57 pm

Suki and JahTeh:

I’ve just seen the completely inexplicable break-up of an Iraq veteran’s marriage.

Some things have improved since the Viet-Nam War but the ADF is a very slow learner.

Weez and Katar:

When I joined the Australian Army way back in the mid-‘sixties, we were all given rock-solid, gold-plated core promises of social mobility. None of us realized at the time that it was indeed social mobility……Downwards!

June 11th, 2006 at 11:15 pm

Oh my…

Thank you for reminding us of the usually hidden, but very personal and very sad reality of veterans unsuccessfully rebuilding their loving relationships after one/many deployment/s.

A job is not a partner.

June 14th, 2006 at 9:03 pm

Suki:

I’ve had a bit to do with veterans of various conflicts: some ancient, some recent; (and no, I’m not trying to argue from authority).

While the after-effects of conflict itself are fairly similar from one war to another …. there are remarkable differences, from one country to another and from one period to another, in how well war veterans are rehabilitated back into civilian life.

It seems to me that recovery is far less dependent on the intensity and duration of the experience of war as on:

(1) Training and other preparation for the experience of war

This is where I was lucky; my own upbringing made me better prepared for the experience of war than did much of my formal military training ….. and sometimes the skills that I had acquired as a kid and which helped keep me alive was contradicted by what was presented in training; I learnt more from “bloody w*gs and balts” than I did from crash-hot spit-polished drill instructors. When the inflexible and arrogant ADF learns to be humble enough to learn from people who have survived wars, no matter who they are, then the ADF will have fewer casualties …. which Australian taxpayers and Australian families have to pay for.

and

(2) The behavior of non-combatants in the home country.

So long as returning veterans are regarded as troubled or trouble-making, as irredeemably brutal and hopelessly unreliable, then the chances are much diminished for them reintegrating themselves into the society that sent them off to war in the first place, regardless of whether the particular war or operation has widespread support or not.

[Furthermore, the Dept. of Veterans’ Affairs and the Returned & $ervices League have as much to answer for as regards war veterans and their families as did the Dept. of Native Affairs and the Churches as regards Blackfellas …. but that’s another story].

You are absolutely right about a job not being a partner….. the same can be said about military service too.